Television

(Hover over/click each banner for more)

(Hover over/click each banner for more)

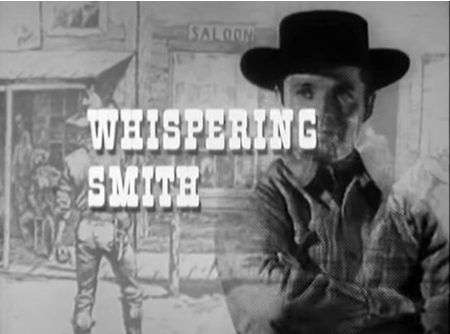

Bloch’s entrance into writing for television originated when friend Samuel Peeples—at the time a writer of western teleplays for such series as Wanted: Dead or Alive and The Rifleman—requested Bloch to come to Hollywood to write a script for the crime drama, Lock-Up. Bloch’s initial submission was accepted and led to additional assignments.

Bloch worked steadily in the medium throughout the 1960s and 70s, writing teleplays for numerous popular and acclaimed television series. With friends in the business introducing Bloch to executives and producers in the industry, he came to Universal Studios in late 1959 and met the staff producing Alfred Hitchcock Presents. Given that the show had produced two of Bloch’s stories, they asked him to write a script, an adaptation of a Frank Mace story which became “The Cuckoo Clock.” Upon delivery of the script, he was offered subsequent assignments, ultimately writing a total of eight teleplays for Presents. Arguably the most notable of these was his own story, “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice.” This episode is (in)famous for not being broadcast during the series original run for its ending being deemed too gruesome (the implication of Diana Dors being sawn in half). The episode later saw its debut on television when the series went into syndication. Bloch would continue to write for the show after its expansion to an hour in length and rename to The Alfred Hitchcock Hour.

During his Hitchcock tenures, he additionally became involved with writing for Thriller (1960-62), a new mystery/suspense anthology series starring Boris Karloff. Through this stint, Bloch first met the famed horror actor, which led to the pair becoming close friends. Bloch wrote a total of seven scripts for Thriller, many adaptations of his own stories. He adapted one story not his own, D.M. Lessing’s “The Black Madonna,” retitled to “The Grim Reaper,” starring William Shatner, which would come to be known as one of the more memorable episodes of the series.

For Night Gallery, Rod Serling’s supernatural-leaning follow-up to his lauded Twilight Zone, Bloch sadly (if ever a show was geared toward his forte!), contributed only one produced entry, adapting August Derleth’s 1939 short, “Logoda’s Heads.” Invited to write a script for the original Star Trek, Bloch ultimately contributed three teleplays: the light-weight entries “Catspaw” and “What are Little Girls Made Of?”, as well as a nod to Jack the Ripper, “Wolf in the Fold.” Here, Bloch transforms “Red Jack” into a non-corporeal entity who takes over the Enterprise’s computer, and thus, control of the ship, before Kirk and Spock save the day.

Bloch additionally wrote the teleplays for two major network “Movies of the Week” – The Cat Creature (1973) and The Dead Don’t Die (1975), the former an original story, the latter, an adaptation of Bloch’s own story of the same name. Both films were directed by Curtis Harrington, a writer and director of primarily low-budget horror and science-fiction films (Night Tide, How Awful About Allan, and others.). Cat Creature was meant as an homage to the spirit of the Val Lewton classic, Cat People (1942), while Dead concerns itself with zombies shambling the streets of Chicago in the 1930s. Neither project left Bloch nor Harrington completely satisfied, due to typical corporate and network intrusion into the scripts.

Bloch worked steadily in the medium throughout the 1960s and 70s, writing teleplays for numerous popular and acclaimed television series. With friends in the business introducing Bloch to executives and producers in the industry, he came to Universal Studios in late 1959 and met the staff producing Alfred Hitchcock Presents. Given that the show had produced two of Bloch’s stories, they asked him to write a script, an adaptation of a Frank Mace story which became “The Cuckoo Clock.” Upon delivery of the script, he was offered subsequent assignments, ultimately writing a total of eight teleplays for Presents. Arguably the most notable of these was his own story, “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice.” This episode is (in)famous for not being broadcast during the series original run for its ending being deemed too gruesome (the implication of Diana Dors being sawn in half). The episode later saw its debut on television when the series went into syndication. Bloch would continue to write for the show after its expansion to an hour in length and rename to The Alfred Hitchcock Hour.

During his Hitchcock tenures, he additionally became involved with writing for Thriller (1960-62), a new mystery/suspense anthology series starring Boris Karloff. Through this stint, Bloch first met the famed horror actor, which led to the pair becoming close friends. Bloch wrote a total of seven scripts for Thriller, many adaptations of his own stories. He adapted one story not his own, D.M. Lessing’s “The Black Madonna,” retitled to “The Grim Reaper,” starring William Shatner, which would come to be known as one of the more memorable episodes of the series.

For Night Gallery, Rod Serling’s supernatural-leaning follow-up to his lauded Twilight Zone, Bloch sadly (if ever a show was geared toward his forte!), contributed only one produced entry, adapting August Derleth’s 1939 short, “Logoda’s Heads.” Invited to write a script for the original Star Trek, Bloch ultimately contributed three teleplays: the light-weight entries “Catspaw” and “What are Little Girls Made Of?”, as well as a nod to Jack the Ripper, “Wolf in the Fold.” Here, Bloch transforms “Red Jack” into a non-corporeal entity who takes over the Enterprise’s computer, and thus, control of the ship, before Kirk and Spock save the day.

Bloch additionally wrote the teleplays for two major network “Movies of the Week” – The Cat Creature (1973) and The Dead Don’t Die (1975), the former an original story, the latter, an adaptation of Bloch’s own story of the same name. Both films were directed by Curtis Harrington, a writer and director of primarily low-budget horror and science-fiction films (Night Tide, How Awful About Allan, and others.). Cat Creature was meant as an homage to the spirit of the Val Lewton classic, Cat People (1942), while Dead concerns itself with zombies shambling the streets of Chicago in the 1930s. Neither project left Bloch nor Harrington completely satisfied, due to typical corporate and network intrusion into the scripts.